At the Photographers Gallery 16th October 2022

Having read a little about Killip’s penchant for capturing stories of people in some of the most run down areas of the UK I was eager to see what was in store for me at the wonderful Photographers Gallery in London.

I walked in and paid for my ticket then spoke to the young guy behind the desk and asked him what the best way was to see the exhibition, he spoke with firm authority and told me that it was best to start from the top and work downwards. The people in galleries are most helpful and have had experience at working with curatorial teams on how to best direct members of the public so I took his word and jumped in the little lift to get up to the 5th floor, John Lyon Gallery.

Greeted by a large Red wall with a blurb about Killip it sets the tone for the rest of the exhibition, the walls are clean and mostly white in colour except for a small number of walls the same red hue as when you entered. These seem to be red for a reason which I’ll come to a little later on.

Killip who was born in 1946 and died only two years ago (2020) amassed a large body of work that has been vaunted all across the world for capturing what he himself once called;

“..real moments in people’s lives.”

Early Days

The show starts with his earliest work between 1970 and 1973 mostly on the Isle Of Man and shows the communities on the island with demonstrations of their pre-industrial revolution farming practices. Many of his portraits of Manx people seem to be really friendly and open for the camera almost as if he knew every single person he was photographing. It’s only a small island I guess so he may have done.

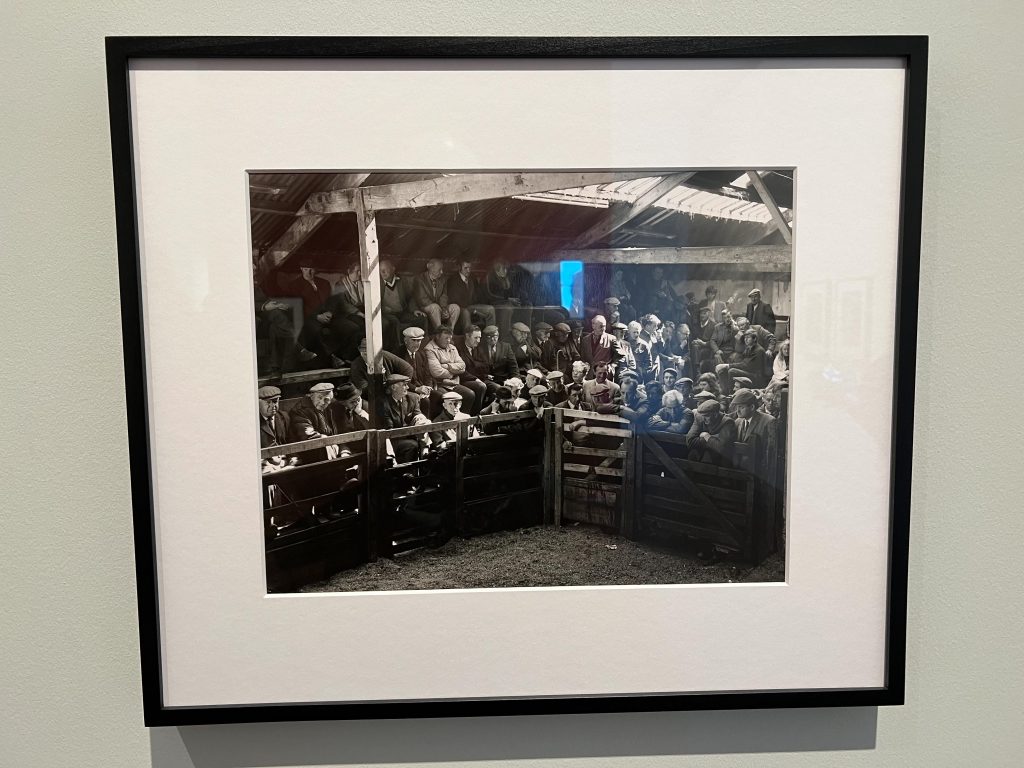

According to the text on the wall, regarding his early years photographing on the isle of Man, he wanted to capture the communities before they were taken over by modern practices. One of his images captures a farmers market on the island, showing around 70 farmers and their wives all waiting by the auction ring for the produce to be presented before bidding gets underway. It’s a great image showing the different ages and classes of farmers at the sale.

To me it’s almost as if Killip has placed his camera in a location to suggest that the market is a place to buy farmers, that they’re being fenced into the back of the building desperate to get into the ring and be taken to a new profession or home.

Moving onto the next section, 1974 to 1977 shows some work from shipyards, and coal mining towns that capture the industrial life of British people in the North East of the country. A particular favourite of mine in this section was “Two Girls, Grangetown,Middlesbrough, Teeside,1976” which depicted a small council house next to some waste land with two young girls sat on the kerb chatting innocently, completely ignoring the behemoth of a coal fired power station amongst other industrial chimneys,, spewing out pollutants into their atmosphere.

It’s a wonderful juxtaposition of the innocence of childhood with the filth of being an adult trying to earn enough money to live. The pictures are all framed in simple black wooden frames and mostly the same size, with an occasional larger format print thrown in. All of the prints are fixed behind glass and a matt to neatly frame the image, except for a few of the really large prints which don’t have a matt. Their print edges go all the way to the frame.

Other images feature smashed and paint splattered bus stops, and Prize bingo parlour all seemingly surrounded by debris and litter. He paints the area completely realistically and in some cases it reminds me of growing up as a child in one of the poorer areas of Shrewsbury.

Also harking back to my younger years in one photo, the first of the large format images I noticed, a young boy sits on a wall in a position that suggests he’s crying with pain or sadness, maybe even hunger. His shaved head might be a way to avoid of “nits” (head lice) and his clothing looks like it’s hand-me-down and very worn. “Youth on a wall” is a stark image, made even more so by the sheer scale of the image. You can see every mark on the boy’s jacket and shoes and I felt moved, almost as though I was stood in front of the young man trying to help ease his worries.

The lack of a mount/matt and the size of the frame enables the image to engulf the viewer and forget that you’re looking at a carefully printed and framed image. It’s as though Killip managed to build a portal between today and 1976 Jarrow.

Well Hung

Each of the images in frames are hung on a centre line, and where two pictures are displayed one above another, the centre line bisects the gap between the two frames. It helps with the clean lines of the show and doesn’t confuse the viewer as to which direction they should be looking at the images in.

The titles are all on the same level and printed directly onto the wall. There is very little text around and kept to the paragraphs on the walls explaining the history of where Killip chose to spend time photographing his subjects.

Pride of The Tyne

Before I leave this North East section I come back to a red wall featuring some images of Camp Road, Wallsend. In the first image from 1975, see below, there are three children playing in the street with a car parked in the background. To the right of the frame is a railway line, unseen apart from the signal, and then past that the huge super tanker Tyne Pride, being built in the shipyard that would have been the largest employer in the area. It’s a lovely image evoking a nostalgia for a simpler time.

The next photo shows the rush of manual labourers heading off to the shipyard to begin their day, in the same area. It’s a time of good incomes and a busy, but dwindling shipbuilding industry. Another couple of images here show the thriving shipyards and the infrastructure placed so close to this neighbourhood. The next photo on the troubling red wall is an image of the same street in winter with no ship in the yard to the right. It’s almost representing the end of the shipbuilding industry and whilst there still appear to be some children playing with a sledge, they don’t look so carefree as earlier images. The wall to the left of the image also displays some graffiti about abstaining from the democratic process and a forthcoming revolution.

As if to contrast this story so far, the exhibition moves the next image in the series onto a white wall at 90 degrees to the previous. This image though shows a 1977 image of the area being demolished. The same graffiti exists, and the Gerald Street sign on the corner of the house shows that this is exactly the same spot, but with no work the area has fallen into ruin and a migration of people to other industries.

It’s a very moving image and whilst for some younger people this may seem like ancient history, I was four years old in ’77 when this image was made. To think that the area is now a commercial area and containing a “Roman” Bathhouse whilst the yards still sit silent, and some of them even restored for tourism purposes. The Tyne Pride was launched from here in 1975 according to the very knowledgeable website: http://www.tynebuiltships.co.uk/O-Ships/opportunity1976.html Somewhat ironically, when considered with this set of images, the ship was renamed “Opportunity” in ’76 and was eventually broken up for scrap itself in 2005.

The image below shows the series of images in the gallery and it’s a strange contrast of where the “demolished” image sits. The curator has purposely placed it here away from the remainder of the images but I can only think that it’s to build you up in hope and then dash them when you turn the corner to see the destruction and dereliction.

Fourth Floor

Making my way down to the fourth I walk into the gallery with some text on the wall stating Skinningrove 1982-1984. This was Killip going to investigate the seaside community with a steel works on the hill above the fishing village which sat on the North East coast. This felt strange as I’d been to Skinningrove once a few years back as my employer has a factory in the area the coastal layout and the view was reminiscent of the short time I spent there and it took me straight back there.

Killip was seemingly impressed by the workers who did a shift in the steelworks before heading out to sea in the small boats to work as fishermen. The photos in this room remind me of the movie “This Is England” and also my childhood again, with the attitude being shown on the faces of the very youthful subjects of the images. There are few images of the older generation and the images on the walls depict the teenagers and young adults as being hard working and having fun together as a real community.

The images here are concerned with capturing the facts of life in Skinningrove and show it warts and all. There are punks with great mohawks, casuals in their Mod type clothing sitting in front of a backdrop of functional housing with no real luxuries to be seen anywhere.

The faces of the people in these photos tell a tale to me of a frustration of living with nothing to do except working and hanging around, there are some pictures of cars which date the images and remembering what I was doing in those days I recall a lot of unrest from young people fighting against Thatcher’s Tory rule over the country. The people depicted here in Killip’s work seem to have resigned to the fact that there’s not a lot they can do to have an effect on the issues of the day.

The photographs in the Barbara Lloyd gallery are presented in the same manner as the work upstairs in the John Lyon gallery. Smaller images in black frames with the white matts in and the larger images completely fill the frame. All are black and white and this seems to add to the grittiness of the contents. Colour may well have been a distraction when the murk of life on the margins of society is apparent.

You can see in my photo above of a typical wall in the exhibition that the titles all remain consistent and the borderless images seem to suck you into the image as if it’s a time portal. I can almost hear the engine of the Ford Fiesta driven by the Fred Perry shirt wearing friend. The main subject with the tattooed next “Bever” has dirty hands and bitten-short fingernails as well as a scruffy hair cut.

Moving

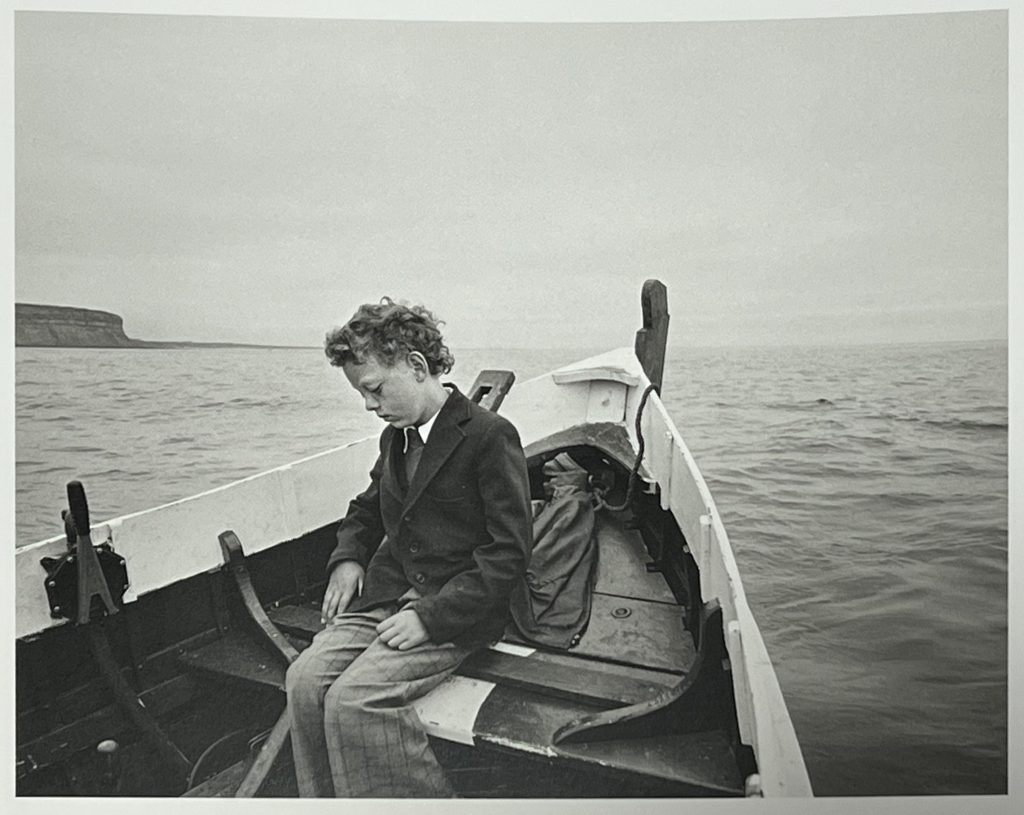

There are also some deeply moving stories in this exhibition such as a 1983 image of a young boy in blazer, tie and trousers going out to sea in a boat for the first time since his father died of drowning. It’s a poignant photograph showing the head-down, heavy eye-lidded figure of the boy seemingly accepting his destiny to follow his father’s footsteps in to the fishing industry but at the same time reflecting on the loss. His hands appear to be preparing to form the usual position for a prayer in my mind and the big open expanse of the sea behind him tells the story in the larger context.

Another moving story is of one of the young men, named Leso, in Skinningrove who died at sea and Killip was able to provide a series of photographs to the parents in an album, Killip thought that if providing these valuable moments captured on film was the only reason to have been photographing in the village then it “was reason enough” (explanatory wall text in TPG )

Seacoal

The Skinningrove part of the exhibition was a good exploration of the lives of the hard working people of this area, and then you walk into the Seacoal part of the exhibition and realise that life can get exceptionally harder.

In this section of the gallery were many images of the Lynemouth area of Northumberland, 75 miles from Skinningrove. Here we see workers using very primitive equipment to harvest coal from the sea. Not something I was aware of before this exhibition but a nearby coal mine must have spilled coal into the sea and then gets washed away for a long time, returning when the winter tides came and washed the coal onto the beaches.

A community of people lived on the shore to wade into the sea and gather up the sea’s gift and get it bagged up ready for sale at a later time. The images here are seemingly more bleak and yet contain some amazing light touches that can be experienced when Killip immersed himself in the environment. (Only after overcoming a suspicion of the purpose of his photography)

Killip in his book “Chris Killip 1946-2020” is quoted as saying that the scene on the beach was “… the Middle Ages and twentieth century entwined” He eventually got himself a caravan and lived amongst the Sea Coalers to gain trust and understand their lives.

Images from this part of the collection show a generally older group of people working in the harsh conditions but there are also children enjoying themselves amongst the background of work, struggle and hardship. One particular image titled “Gordon on Critch’s cart, 1983” shows a man driving a pair of horses and a cart through the breaking waves at the shore and he stands tall whilst holding the reins.

The image contains such wonderful details and the splashing of water against the cart but when I stood back from the wall I was instantly reminded of classical art pieces featuring Roman chariot drivers or God like characters such as Apollo driving their divine chariots through the clouds as can be seen in Luca Giordano’s “Apollo in his chariot” c 1685.

The humanity and humble nature of Gordon is a long way off from Apollo in the above painting but the photo depicts him as a leader of men, a her and someone making his way through life’s troubles with aplomb.

Other images show the humanity of the people on the shore, it shows their lives and all of the fun they have as well as the desolate appearance of their “neighbourhood”

Caught In The Act

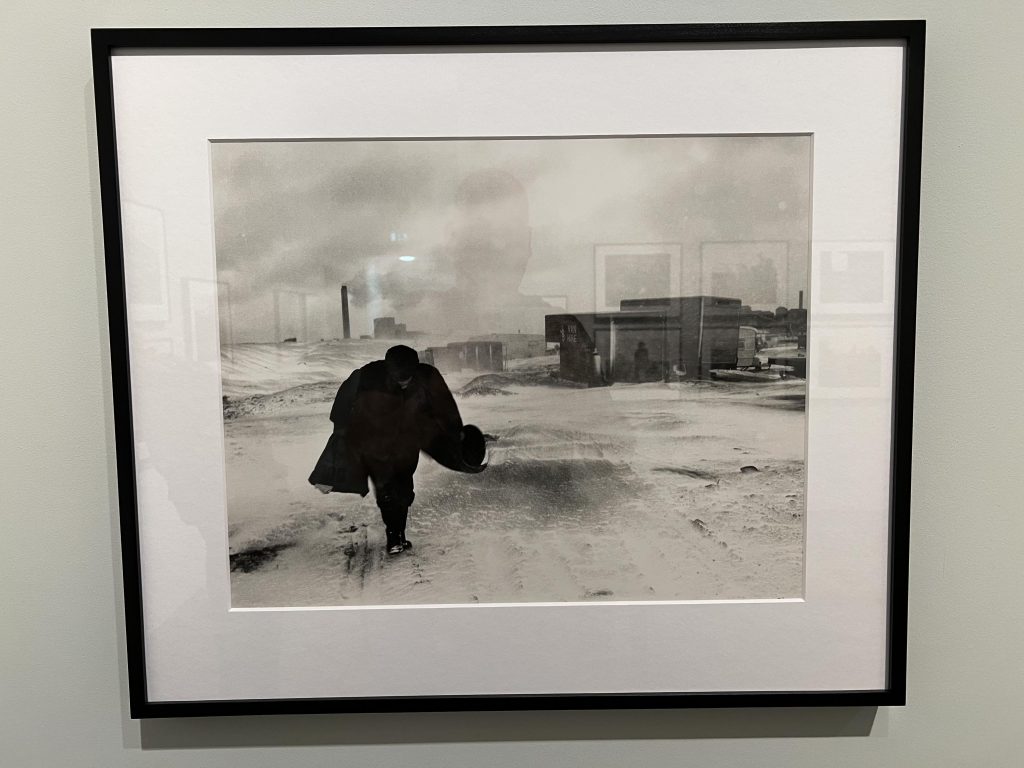

The last part of the Killip Retrospective was titled In Flagrante and saw a collection of images on display from Killip’s book “In Flagrante” from 1988. It contains a wide selection of images from Miners Strikes in Newcastle to others in and around Tyneside showing the decline of the working class in Margaret Thatcher’s Britain. There are photos of punks and skinheads in “The Station” club moshing around with Killip almost capturing the flob (spit) being gobbed around the room so much so that I almost stepped away from the images.

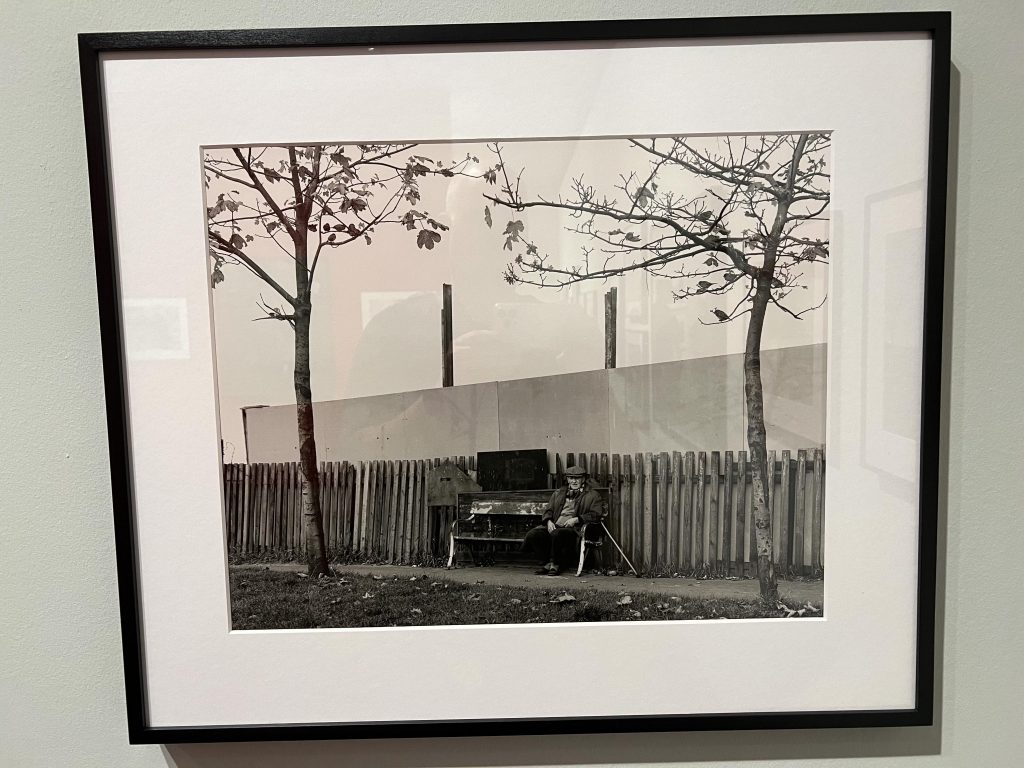

Other images that entertained me included “Man on a bench with fourteen sparrows”, see below. An image that shows an old gent wearing slippers on a bench with the background of a temporary fence providing some great leading lines. Only the title gives away the presence of the small birds, if one looks at the image quickly, this detail is lost. The mere fact that this is the title indicates that Killip intends the viewer to find every single sparrow in the confusing branches of tree branches and leaves. Almost like a “Where’s Wally” puzzle book page.

I wonder if Chris Killip spotted the birds at the time of taking the image or whether it was during the printing and enlarging that they came to be noticed and then was a detail that he couldn’t not refer to, or whether the image was captured because of the birds in the tree sitting there along with the chap on the bench. Maybe even sparrows were out of work int eh troubled times of the early 80’s.

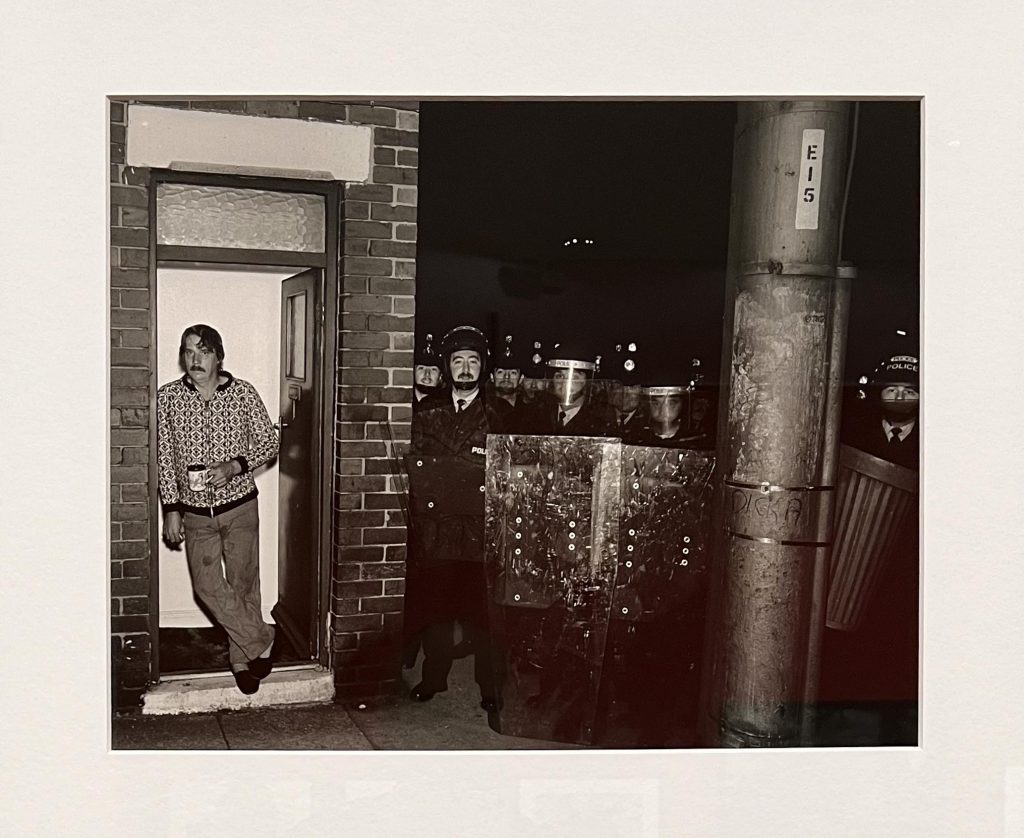

A great image that will forever remind me of this exhibition can be seen below titled “Durham miners’ strike, Easington, Co Durham, 1984”

This image had my full attention as I examined the nonplussed look on the face of the local with stained trousers, stood on his doorstep with a cigarette and a cup of tea whilst the boys in blue, in full riot gear, assembled next to his house. The expressions of the policemen are also intriguing with some of them appearing to be looking curiously at the camera, one or two even smiling. I was fully engaged when a group of enthusiastic exhibition viewers walked aup alongside me exclaiming “No way, how on Earth did he manage to get that picture?”

My view on this and something that can be borne out from all of Killip’s images in this exhibition is that he was in the right place at the right time. He knew where he needed to be and how to get involved in the scene to intimately understand the strife and lives of those he photographed.

It’s a good reminder that one has to be in it to win it, be on the scene or miss the shot. Killip certainly captured many impressive moments in his work and it will inspire me to capture details and moments as he once did.

Summary

The exhibition is an amazing collection of the works of this talented photographer, well presented with no wasted space. In common parlance it’s “all killer, no filler”, every image has a purpose and fits right in to the narrative of the story he was authoring throughout the projects.

Considering all of the images together does not result in a confusing and coagulated mess but a truly time travelling adventure through a bygone, yet very recent to some, age. The Chris Killip Retrospective is open until 19th Feb 2023 and I’d recommend it to anyone.

Inspiration was available by the cart load from this exhibition and it’s a body of work I can look back into with my purchase of a book containing many of the images and more.

The Photographer’s Gallery has pulled off an amazing show with this exhibition and that’s not all, the gallery also featured An Alternative History Of Photography, works from the Solander Collection and A·kin: Aarati Akkapeddi , more of which I’ll cover in a later post.

Comments are closed.