Sylvia set us a mission to read the text by Martha Rosler and make a note of our thoughts on the subjects discussed therein.

According to Aperture online magazine:

The term “post-documentary” has described many things, including a photography that examines these issues of authenticity and power. It now frequently refers to a poetic or ambiguous style whose meaning or message is not overdetermined.

Lucy McKeon, Apri 2021

For me this definition reads as the fact that today it is concerned with photography that documents an event, a people or subject with no overt direction as to what you should think. Whereas in the recent past, documentary had been designed to affect the viewer in a pre-determined way, if possible. Whether the contents or context of the images made were manipulated or posed to provide a narrative to suit a cause or whether there was accompanying text or captions etc. to do the same.

Essay Study

In her essay “Post Documentary, Post-Photography” Rosler discusses the real and the truth. the photographer and the “others”, victims and victimisers, reality and art, war photography, marginalised groups and stereotypes or ethnographics.

Rosler begins with an anecdote of a friend praising the documentary process for “humanising the so-called Others” , regarding transvestites and transexual prostitutes of colour documentary work she’d seen. Rosler argues that the bright and engaging images created a view but for viewers to connect with the subjects was still to big a divide to leap across.

Her friend then asked if the photographer had been living in the community, might it make it more authentic. Rosler argues that “a photographers intentions are unrecoverable from most images” which I take to mean that person taking the photo can be viewed in many different ways by different viewers and not all of them are perceived to be good intentions. Some photographers for example can be accused of promoting a “carnival sideshow” series of images without the viewer understanding what sacrifices were made or efforts to integrate and understand the community.

These misunderstandings can be resolved by including text around, or even in the images to remove ambiguity. With Anthony Luvera’s work with the homeless people, he took quotes from them to sit alongside the photography, explaining about the power dynamic and empowerment of the subjects, but this might not work in all cases. Having explanatory text does not guarantee that all traces of ambiguity are removed.

Rosler goes on to comment on the differences between still images and moving pictures (film and television). She believes that moving pictures are more powerful than the still photos to help viewers understand the differences between the subject and the viewers but both may still be ineffective at bridging this comprehension gap. This is the point she mentions Ethnographic images which take a whole group of people and puts it into one person/subject in a single photograph. We see this in stereotyping often in movies where a character walks into a pub in Ireland and they’re singing songs and playing the fiddle, or a French character wears a striped shirt and beret. The same is done for marginalised minorities, often for the right reason but with an ill effect.

Truth or Dare

The author then describes how documentary, journalistic and news photography are designed to pull in the viewers to a rolling news show or newspaper circulation numbers, not necessarily for a good purpose. Sometimes it’s used to rile up a group of people against another group, we see this in modern politics with sleaze and personal attacks in the news from politicians or even events like MP’s expenses, “partygate”, Brexit and all manner of other subjects.

Interestingly she uses a sentence containing “apparent truth value” which dictates how effective some methods are at getting a particular point of view across to the viewers. She calls it apparent truth, and not truth I think because there is always the element of manipulation that we discussed asa part of Victor Burgin’s “Art, Common Sense and Photography” so there is always a chance that the truth is not fully being passed on.

This goes into the next paragraph where she mentions that there has been “little reason to question photographic accuracy” and “many reasons to accept it. Here we read that she thinks of documentarians that are dramatising or concocting a narrative to make the end result more saleable to a network or institution. Mentions of impeachibility of photographs is made in relation to the computer programs that in 2001, when the text in this essay was reviewed last, were starting to improve at manipulation of photographs. Photoshop was created in 1987 but wasn’t in use by the millions of photographers, artists and designers that it is today. In 2001 though it was already being used to create spoof images and one fo the major events of 2001 was the 9/11 attacks in New York. Conspiracy theories were abound after this, and many photographs have had their veracity questioned as is the same with some of the videos from the time. Many viewers chose to disbelieve the “truth” on the news channels, instead believing the poor quality videos being shared online in forums etc. This was still four years before Youtube was created.

Rosler picks out still images as questionable but in the years since we have seen massive improvements in the ability of video editing software to alter video imagery. On the page in this area I made a note regarding AI and the difference this will make in being able to distinguish the true images/videos from the fake and manipulated. BBC News channels now have a verification team that are tasked with seeking out the truth from the fiction and this will be a part of all organisations that use images and videos in news articles. This is “post-photography” and results in photographs being an art from instead of a truthful document.

Reality Street

The author moves from this place into a world where print journalism is far less prevalent and the “real” is now “refracted through the distorting prism of sensationalism, voyeurism and …. neo-gothic sensibility”. She is of course referring to the television programmes known as Reality TV. In the UK we have Big Brother, The Only Way Is Essex, Benefits Street, Ambulance, 24 Hours in A&E to name a very small number of shows that are regularly shown to audiences. THese purport to be “reality” but are anything but. Firstly the people in front of the cameras, know they’re being watched so will act unauthentically, then the editors and directors of these documentary style programmes are manipulating footage and using some scripts to produce an output that is something viewers want to watch. Imagine an episode of 24 Hours in Police Custody where nothing happens, it would not persuade viewers to tune in next time. These themes are all based around what the audience want to see, what is in the news at the time, what political events are occurring, the state of the economy and NHS for instance will all lead the producers to alter the output to suit.

Rosler discusses “ghoulish addiction to misery and woe” featured in photos of the world outside the studio, particularly aimed at war photographers. She mentions that photographers are accused of this type of work but the work is simply a real image of a real place at a real moment in time. Eugene Richards made some important work on the social effects of crack cocaine and was accused of racism, by focussing on the communities he did. The issue was that photographing and presenting these images might exacerbate the stereotypical view that African-American people were more likely to be engaged in crime. This has been seen in many pieces of work since, and I’ve seen countless discussions in photographic forums, blogs and websites about why photographers do not photograph disabled, poor, and the homeless people in society.

Ethically Speaking

Ethical choices about how to portray subjects must be made by the photographer at the time of the image being made and also at the presentation stage. Thought given to whether the subject might feel slighted or mis-represented must surely cross the artist’s mind and a furious backlash is almost guaranteed if the choice is perceived as ill judged. An example in the text relates to a piece of copy about coffee and it’s route from field to table. The photographer and journalist went back each step of the way and worked together with all parties to ensure they were represented in a fair and thoughtful way. This is an effect of outside photographers, ones who are not part of the community or experienced in the same lived experiences. She goes on to mention that photographing socially disempowered groups might provide a positive benefit in the presentation, even if the subjects feel that they do not wish to be photographed.

Rosler also argues that the best place for a documentary photographer is on the outside of the community for maximum independence but this often leads to ethnographic representations that paint the wider community with the same brush. If there is no text accompanying the photos then they can be interpreted in a multitude of ways, some correct and some less so. This can be seen in works by many photographers, both well known and amatuer. Some photographers will dress a person up according to their perceptions of their background, or history and whilst this sort of stereotyping is decreasing in some areas of society, this is not so everywhere.

An interesting point was also made regarding Arthur Rothstein’s image The Dust Storm (1936) which was a record of an event, which went onto become a news image, a historical photo and now a work of art. The subject int he photos was important early on but the meaning of the image has faded over time and what might have been a strong record of a poor farmer and family is now a look back into history that seems hundreds of years ago. It is true that photos of real life today will be looked upon as a historical record in the years to come. I was interested during covid in catching images of people, including me, queueing at the supermarkets, spaced out at 2m apart, with green and red lights on the doors to allow access. At the time it was strange and documenting real life, but even today it feels such a long way away. In a hundred years time, it will feel like the spanish flu and what we think of that today.

Getting to Know You

The next page sees discussion of the two photographers Hine and Riis. The latter was of the school of evidentiary images which he took himself alongside police actions that were explored and explained by the images, without any involvement in the community as such. The former, Hine took a different path and spent time getting to know the subjects of his images, in the case of a child labour series he got to know their names, ages and occupations then included this detail in the text to accompany the messages he was trying to get across and a dignified representation of the subjects.

Riis and Hine both captured images of people being put upon by society but Riis’ images were of people being caught in the act of something illegal and was full of images of people in terrible environments being subjected to terrible situations where Hine’s images appeared to be more controlled and directed. Both though were unable to say to the subject that their help in the project would have a positive impact on the cause being discussed in the images. It does not make one better than the other but in the days since both photographers have found their work to be held up as. model of different documentary styles.

Paul Strand, who had been a student of Hine, produced works of poorer people in the city of New York and used trick cameras to take a photo without being spotted. This means that there was no voluntary collaboration from the subjects but the images were as real as could be due to this. The people he captured on film were the true people in the streets and roads of the metropolis and he wanted to capture them in all of their ugliness/glory. Despite not having any collaboration in these works he wanted to “afford. them respect through full incorporation” or present them as they actually are and not as he thought they should be presented due to pre-judgment.

Victimless Crime

Rosler goes on to mention Victims and Victimisers next, and refers to the photographer as the expropriator and the subjects as expropriated. The dictionary term for Expropriate is “to take somethign from the owner to use fo the public.” In this cae photographs of the society’s losers or victims taken by the “winners” of society. Interestingly she goes on to say that we are all victims when it comes to photogrpahy, but if we are all victims, who are victimisers. Talks around this result in an ambiguous senase that there is no right or wrong of how to make photographs and display them but we know inherently that this is not true. Inequality might be created by capitalism but it requires systems so that there is a path to equality, and this is quite a profound statmeent to me. It’s saying to me, that without naming and categorising everyone into conveninet collections that we will always struggle to affect change. After all, if we can gather in groups to achieve a revolution it’s usually as a group of communists, people of colour, sexualities and even trade unions.

Ink-Credible

The next topic to discuss is credibility and along with the trust of the photographer we must also trust the medium of distribution. As discussed earlier the period of more distrust in photos and videos is now upon us and increasing with the Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools available at our fingertips. Dall-E and Chat GPT from Open Ai being but two, and Bard from Google all allow us to have work created without doing anything but provide a prompt for the AI algorithm to use and tailor the final piece.

Snapshots, which Rosler considers as “Artless” were previously avoided as cliche’d shots but are now being sought for their honesty and veracity. These types of images are all over the internet today, which was already expanding back in 2001, and as well as the photos with snapchat filters of cat’s whiskers and ears, there are countless honest self portraits “selfies” that speak to the truth of the person photographing themself or their families with the front camera. The mobile phone, smart phone and camera phone have all gone to expand photography into everyone’s lives. Most of these images and videos though are colour.

Rosler mentioned that in the early days of colour photography and printing, it was considered as an affront to serious photography, before photographers like Saul leiter, and William Eggleston started using the format seriously. Serious new photography might have been considered more truthful if it were in black and white as was previously the case for all news papers. Nowadays though it is more likely to be colour than black and white Black and white imagery almost being considered the Arty side of photography.

As well as the black and white images being considered more serious, they were also made by serious journalists in serious situations and published in serious magazines or news journals making them seem even more credible. Rosler mentions that the documentarians responsibility is to society and as such should be objective in their practice, then allowing the journalists writing the copy to provide the opinion, but if the person behind the camera is different to the person behind the word processor keyboard, it can sometimes result in images being misused and lead to ill feelings or misunderstandings.

Street Reality

Street Photography is next on the agenda in this piece and how there is no responsibility to the subjects of the images. Often seen as outsiders trying to make a fast buck from exploiting these people going about their daily businesses, Street photographers are often sneered at. Part of this bad reputation comes from the power differentials caused by photographers not getting involved with the subjects, as per Hine’s trick camera, and this leads to people feeling used. Without street photography though, many important events would not have been captured for posterity. She says that Street Photographers are often taking pictures that are a representation of themselves and the baggage that they carry around with them in their psyche.

The street photographer links into the next page and how some photographers feel they need to inject themselves into the society or group, a good example of this is Anthony Luvera who we studied briefly last week and how he spent four years integrating into the homeless community he wanted to make portraits from. The street photographer on the other hand is what Rosler terms “parachuting photojournalist” i.e. they’ve just dropped in on the ground and are ready to shoot photos without spending time engaging with the environment and people around them. This is what I do as a street photographer really. I do sit and take time to see where the best spots might be and I don’t really care what class, category, label or any other defining characteristic they bear. If it’s an intereseting shot to me I’ll press the shutter. Luvera gave the subjects the shutter release in his series “Construct”.

Rosler goes on that giving people the agency to make their own work, wither by providing them resources to do this, will often lead to more present style photos, in that the subjects are not bothered by a professional photographer but they will still be interested and possibly change behaviours in front of the camera. The difficulty with this method of photography means that the photographs may not be well taken, because it’s not technically a photographer and as a result the images may be imperfect. Going back to the “snapshots” comment earlier though, maybe this lends even further credibility to the images created. Another downside of this is that a personal testimony or quote is also required to put the image into some sort of context for the viewer to make sense of.

With external photographers comes the danger of the perception of voyeurism and sensationalism, as discussed earlier in this post and is used to interest people or galleries in purchasing the art in question without much thought for the result of the work being displayed or collected.

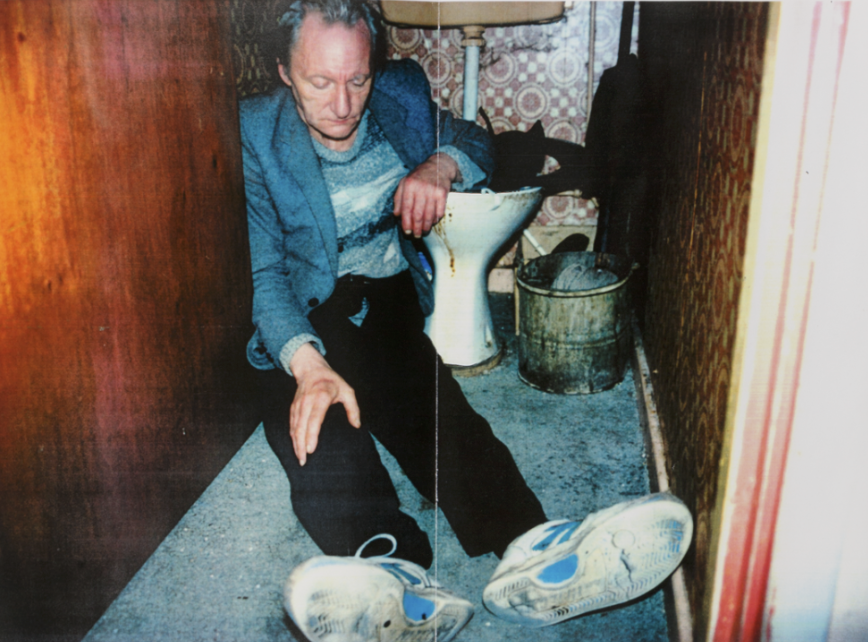

In the next paragraph Rosler discusses Richard Billingham, who we’ve met in the book Ray’s A laugh, and his “de-skilled, slacker aesthetic” as he puts it. His pictures of his poor family in a council flat in the West Midlands appear at first to be simple snapshots of his parents and his family telling an important story about his life. She sounds disappointed that Billingham was sought after by Saatchi and a “hungering pack of international collectors” as if his photos were not worthy of the attention. To me they represent real life for many peopl ein the country, and around the globe. Growing up in similar circumstances, these images spoke to me, and although Martin Parr is often derided of r mocking the poor people, his images also speak to me of my childhood. I do not feel mocked by either artists’s works but a sense of nostalgia and a movement to educate people that we don’t have to live like our parents.

The ;ast point Rosler makes in the essay is about how she thinks that true life documentary will be overtaken by politically correct and socially responsible documentaries. She says that there is a “loss of stable avenues of dissemination” but I’d argue that there are far more methods to self publish important works on the internet or even in cost effective book formats.

Summary

For me this essay by Martha Rosler is a good investigation into documentary photography and journalism. The reasons why some methods work, and some less likely to work and the results of what looks like success and failure.

She discusses the different methods of taking photos, from within the community, from outside the community or getting the community to photograph themselves. The positives and negatives of each are discussed with a pretty even split depending on which side of the dividing line you stand. These dividing lines are drawn by our own lived experience and also our prejudices and prefereences for the subjects in the frames.

The distribution and publishing of the photos is just as important also and whether it requires explanatory text, quotes etc compared to whether they should be left text free for the viewer to make up their own mind.

She uses the term Post-documentary to describe what comes next, after the early days of documentary when the stories morals and goals were practically forced down the viewers’ throats. Today it’s more about getting the intellect of the viewer to tease the facts out of the photos, whether it’s accompanied by text or not.

A lot of the writing in the text made me feel a bit dull and I had to re-read many sentences and compare to other parts of the text, the dictionary on my PC and also the internet.

At the end of the essay she includes photos from documentary photographers in which some are shown with quotes from the subjects, some with poetry that does not appear to be linked to the image or nothing at all.

For me, taking photos of people in candid situations is always the method I get the most true images of a person or a community. It doesn’t mean that I’m being a voyeur or a bad photographer, it just means that I want my work to be authentic and not shaped by the external forces at play.

There are though, some internal politics and prejudices, or unconscious biases at work in my mind that mean I do pick some subjects or situations over others, what these are I do not know. I do know that I take pictures in a democratic fashion, I don’t solely concentrate on young women, old frail men with walking frames, homeless people sleeping in doorways or disabled people trying to get around the town centres. Do I consider myself a documentary photographer, yes I guess I would. Do I have any motives though? Nope, not really. I take photographs of scenes that interest me, I don’t have any allegiance to get them published in a magazine or a gallery, so I’m not being driven by money, fame or anything else.

For the use of Post-Photography, she was ahead of the curve by over 20 years. There is a large concern that AI will indeed be able to take the jobs of real photographers and be able to produce images based on the story. But is this the truth? Will people ever be happy that it’s not a real photo of the events at the time? Personally I don’t think so, AI is trained up on the work of photographers that have shared their work online or it’s been scanned in from books. If we stop using real photographers, photos will never change again, they’ll be stuck using the same old images to produce the new content and this will surely get tiresome after a while.

Be First to Comment